Why the 20% Rule Fails Laboratory Animals

A Number That Became Dogma

Ask any researcher working with laboratory animals when an experiment should be terminated for welfare reasons, and you will likely hear the same answer: “When the animal loses 20% of its body weight.” This threshold appears in ethics applications, institutional guidelines, and regulatory documents around the world. It has become so deeply embedded in research practice that few people question its origins.

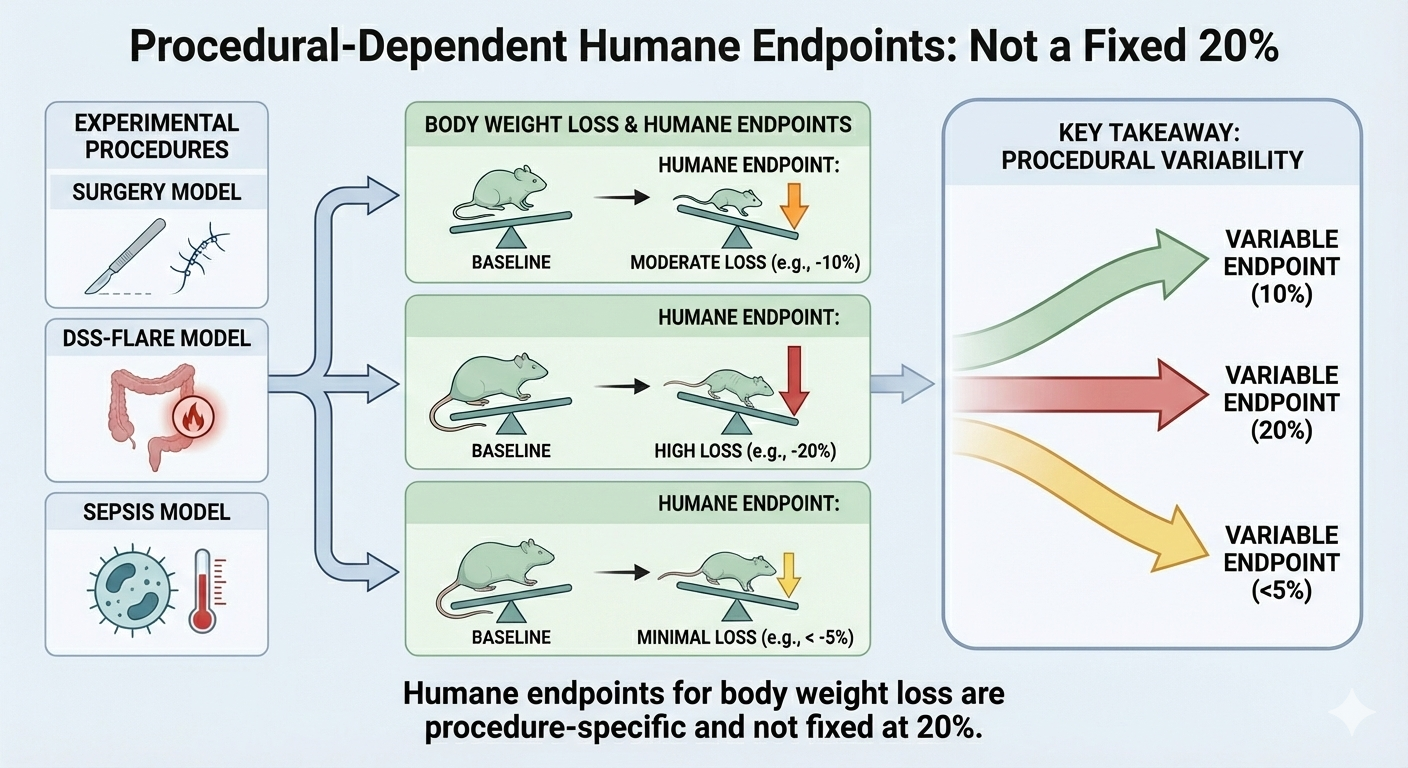

The uncomfortable truth is that the 20% rule has remarkably thin scientific foundations. It traces back to a 1985 publication by Morton and Griffiths, who described a weight loss of more than 20% combined with cessation of eating and drinking as a “starving condition.” Over the following decades, this observation transformed into a universal endpoint criterion, adopted by institutional animal care committees across continents. The EU Directive 2010/63/EU demands humane endpoints but does not specify percentages. Supplementary guidance suggests considering euthanasia at 20% weight loss, with 35% described as an “extreme endpoint requiring sound scientific justification.”

But does this number actually protect animals? A collaborative study across multiple German research institutions set out to answer this question by examining real data from diverse animal models.

When 20% Comes Too Late

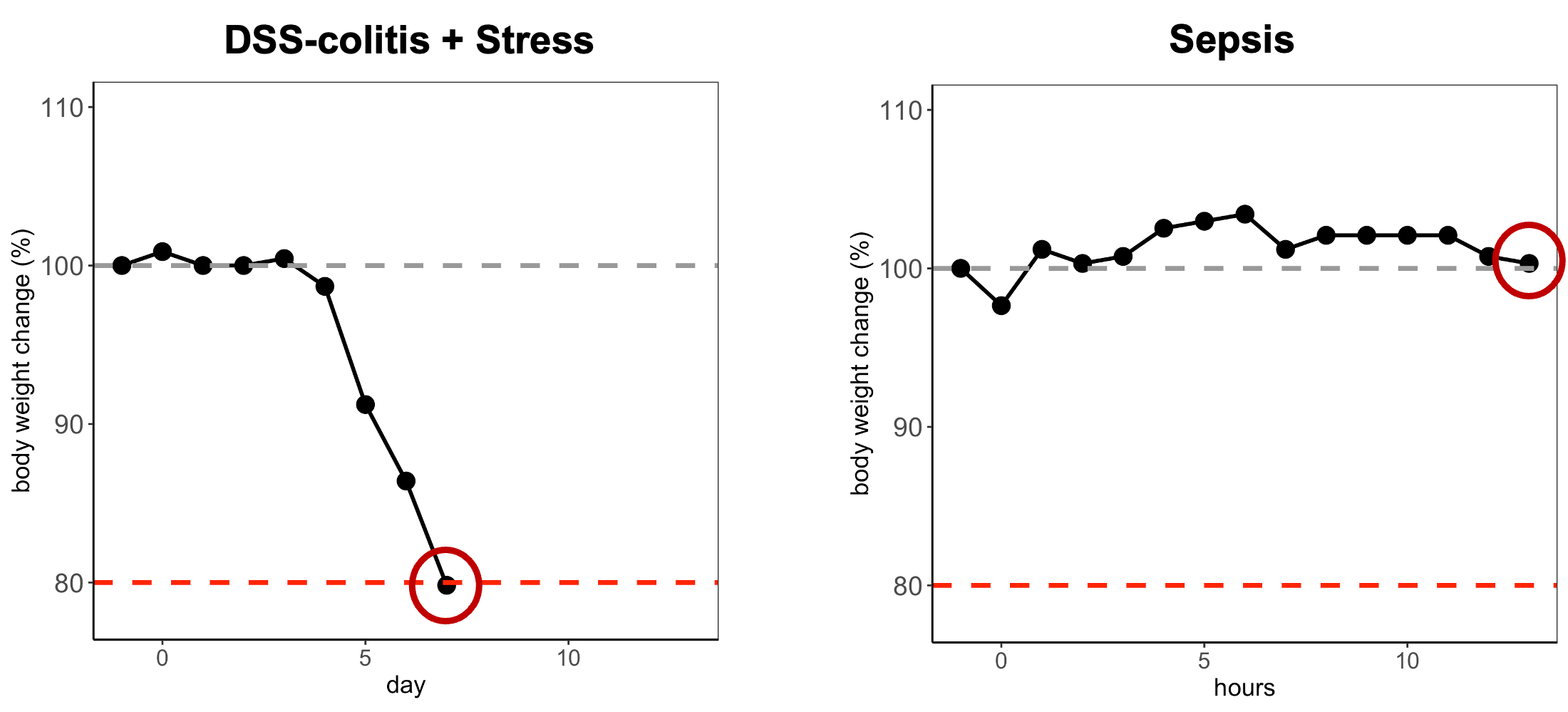

In some disease models, waiting for a 20% weight loss threshold means waiting too long.

The intracranial glioma model provides a striking example. Rats with implanted brain tumors remained in good health for most of the experiment, with a mean survival of 16 days after surgery. The critical deterioration happened rapidly at the end. A mean weight loss of just 2.1% compared to the previous day, combined with slight changes in clinical condition, appeared approximately two days before the animals reached terminal decline. The following day brought severe deterioration with 5.2% weight loss. Animals that would have been protected by a 20% threshold were already in crisis at less than half that level.

In this model, the trajectory of weight change matters far more than the absolute percentage. A rapid decline of a few percent signals imminent collapse. A fixed 20% rule would offer no protection at all.

When 20% Comes Too Early

Other models reveal the opposite problem: animals exceeding 20% weight loss without significant distress.

In a streptozocin-induced diabetes model, mice developed progressive weight loss due to metabolic changes from pancreatic damage. Eight out of thirteen animals lost more than 20% of their body weight within two months. Yet their clinical scores remained remarkably low, never exceeding 5 on a scale of 37. These animals showed no major signs of suffering. More remarkably, mice that were not euthanized began regaining weight from the third month onwards, even as their blood glucose continued to rise.

A similar pattern emerged in acute colitis. Mice exposed to 1.5% DSS in drinking water showed pronounced weight loss, with two animals exceeding the 20% threshold. But their clinical presentation remained mild. Bloody diarrhea was essentially the only symptom. Within days of DSS removal, animals began recovering.

In both models, strict application of the 20% rule would have meant euthanizing animals that were neither in severe distress nor approaching death. This represents an unnecessary loss of animals, directly contradicting the Reduction principle of the 3Rs.

The Complexity Behind a Simple Number

Why does the same percentage mean such different things in different contexts? Because weight loss is not a single phenomenon with a single cause.

Body weight can decline for many reasons. Fear, pain, and distress-reduced appetite. Disease progression increases metabolic demands. Inflammation causes malabsorption. Certain drugs affect energy expenditure. Caloric restriction studies deliberately maintain animals at lower weights for extended periods, sometimes showing health benefits rather than harm.

The diabetes and colitis examples illustrate metabolic and inflammatory causes of weight loss that do not necessarily correlate with suffering. The glioma model shows how aggressive disease can kill before arbitrary thresholds are crossed. Surgical models like liver and pancreatic resection demonstrate transient weight loss followed by complete recovery within days.

A single number cannot capture this complexity.

What Actually Predicts Welfare?

The study’s findings point toward more nuanced approaches. Several factors matter more than absolute weight loss:

Rate of change: A 5% loss in 24 hours signals acute crisis. The same 5% spread over two weeks may indicate gradual adaptation. The glioma model demonstrated that rapid daily changes predict clinical deterioration far better than cumulative percentage.

Clinical context: Weight loss accompanied by severe clinical signs demands immediate attention. Weight loss with normal behavior, activity, and appearance may warrant monitoring rather than intervention.

Model-specific knowledge: Researchers who understand their disease model can predict which animals are likely to recover and which are entering terminal decline. This expertise is hard to replace with a universal number.

Individual trajectories: Comparing each animal to its own baseline, rather than to a fixed threshold, captures deviation from normal more sensitively than population-level rules. But this may also prove difficult in longer experiments where age-dependent weight gain is confounded with possible weight loss.

The Path Forward

The study’s authors are clear in their conclusion: “The decision for euthanasia should not be based solely on an arbitrary percentage of body-weight change, but should always consider other parameters indicating pain or distress and also animal model specific considerations.”

This does not mean abandoning structure. It means replacing rigid rules with informed judgment. Weight loss remains a valuable welfare indicator, easy to measure and objectively quantifiable. But its interpretation requires context. A flexible implementation, tailored to each experiment and each model, serves animals better than universal thresholds that fit no specific situation well.

For the 3Rs to function as more than principles on paper, we need endpoint criteria that actually protect animals when protection is needed, while avoiding unnecessary termination when animals would otherwise recover. The 20% rule, applied blindly, fails on both counts.

The question ethics committees and researchers should ask is not “Has this animal crossed a predetermined line?” but rather “What does this animal’s condition tell us about its welfare trajectory, and what does our knowledge of this model predict about its future?” The first question has a simple answer that may be wrong. The second requires engagement and expertise, but it is the question that serves animals best.

Want to learn more? This post discusses findings from a multi-center study and related tools for evidence-based endpoint detection: